MEMENTO C

CONTACT

MEMENTO C

CONTACT

MEMENTO C

CONTACT

MEMENTO C

CONTACT

概要

Japanese Overview

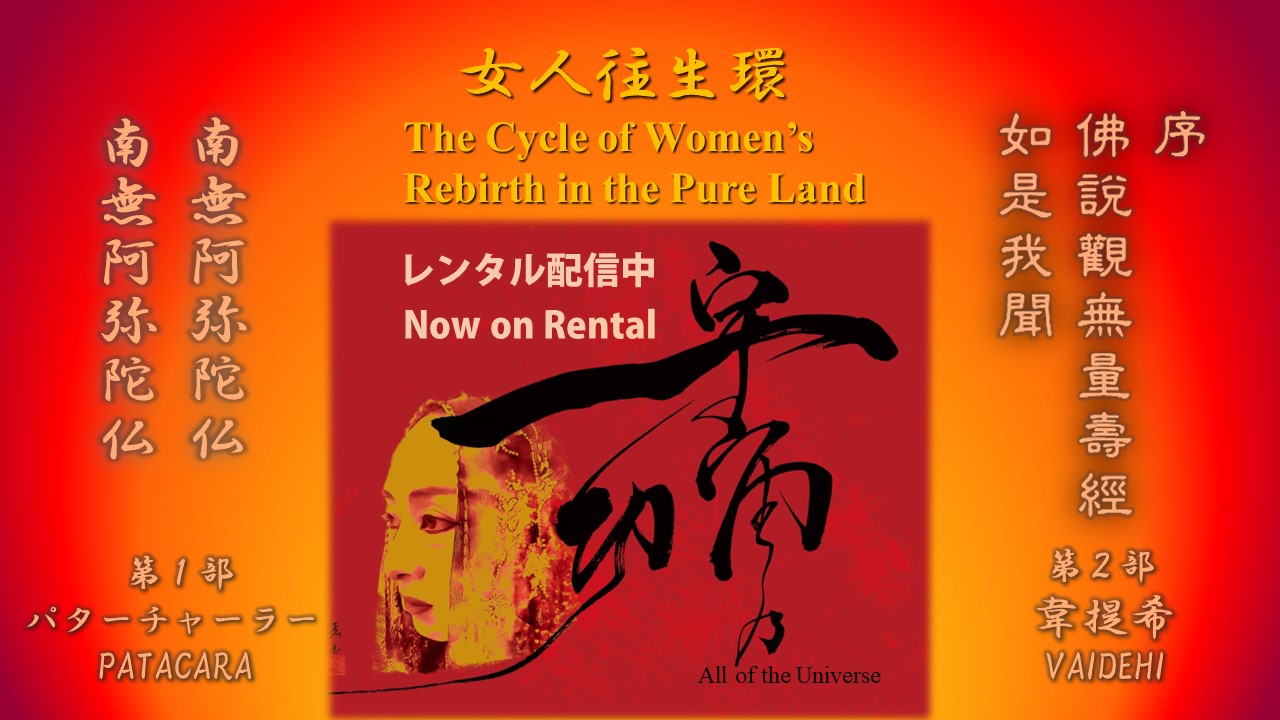

古今の女性の物語を女流邦楽演者による生演奏とともに上演し、“女人往生成り難し”をアーティスト、ジェンダー研究者、観客が思考する試み。

第1部 舞踊劇『パターチャーラー』~哀れ女人、その苦しみの源は~

第2部 現代能『韋提希(いだいけ)』~なぜ生まれた? なぜ産んだ?~

2020年に女人往生環プロジェクトに賛同したオーストラリアの日本文学研究者:青山友子(クイーンズ大名誉教授)とバーバラ・ハートリー氏の共訳によって、「パターチャーラー」「韋提希」の二作品が英語翻訳された。「パターチャーラー」では、能楽の四拍子の囃子と、地謡がストーリー・テラーとなって、波乱万丈の物語を進める。義太夫三味線(鶴澤津賀寿)は、インド音階を用いた特徴のあるコードを奏で、豊かな湿潤なインドの森を三本の絃によって描写する。これらの邦楽は囃子方である堅田喜三代(劇団新派所属)のプランニングによるものだが、日本の邦楽界において、能楽や歌舞伎の「本公演」では、女性奏者の活躍の場はまだ少ない。劇中、囃子だけでなく、多様なパーカッション・アンサンブルが、盛り込まれ、劇世界を構築している。

概要(英文)

English Overview

An attempt by artists, gender researchers, and spectators to think about "Difficulty of female Buddhahood" by performing stories of women from ancient times by female traditional japanese musicians.

Vol.1 PATACARA -- Pitiful woman, the source of her suffering --

The love-loving beauty Patacara loses all of her wealth, family, and good looks and is rescued by Buddha.

Vol.2 VAIDEHI -- Why was he born? Why did you give birth? --

From the Buddhist theory ”Tragedy of Rajagaha”

A modern story of a child who was stigmatized before he was born and his mother's relief.

Historically, a vast amount of culture, including writing, religion, and art, flowed into the Far East island nation of Japan from Western Asia via China, the Korean Peninsula, or Indochina. And some strands of it continue to have a major influence on the legitimization of the oppression of women in the 21st century. This project visualizes two stories created with a woman depicted in Buddhist scriptures as the heroine by using traditional performing arts, contemporary theater, and physical expression to create a three-dimensional work.

Two works, "Patacara" and "Vaidehi" were translated into English by Tomoko Aoyama (Australian scholars of Japanese literature and former professor at Queen's University) and Barbara Hartley, who endorsed "The Cycle of Women's Rebirth in the Pure Land" project in 2020. In "Patacara" the four-beat Noh musical accompaniment and the jiutai(songs in Noh) act as story tellers to advance the tumultuous tale. The gidayu shamisen (Tsuruzawa Tsugaju) plays a distinctive Indian scale chord, depicting a rich, moist Indian forest with its three strings. These Japanese traditional music performances are planned by Kisayo Katada (a member of the Gekidan Shinpa), a musician, but in the Japanese traditional music world, there are still few opportunities for female players in "main performances" of Noh and Kabuki. In addition to the musical accompaniment, various percussion ensembles are used throughout the play to build the world of the play.

公演情報

Performance Information

2019.11.07 - 2019.11.08

座・高円寺2

作・演出:嶽本あゆ美(メメントC) Written and directed by Ayumi Dakemoto

邦楽:堅田喜三代

舞台美術:中川香純

照明:芦辺靖

衣装:中村里香子

舞台監督:逸見輝羊/今宮稜正(stage company)

演出部:大内史子

制作:奥田英子(G-com)

制作協力:竹内洋(株)Hermann MacCartney

宣伝美術:高畑朝子

書:飯田麗玉

翻訳: 青山友子/Barbara Hartley

スーパーバイザー: 柳沢晶子 Mu-arts

協力:光照山 西徳寺/銕仙会/月白亭 杉田 光照/劇舎カナリア/あるでばらん 唐組/劇団椿組/青年劇場

共催:婀の会

助成:芸術文化振興基金助成事業

協賛:岡田屋布施/「音を抱きしめるプロジェクト」プロデューサー西口久美子

出演:観世葉子/山本健翔(劇舎カナリア)/なかええみ/杉嶋美智子(メメントC)

能楽 柴田稔/伊藤嘉章

囃子 堅田喜三代/望月太左乃 望月太左衛

笛 鳳聲千晴

義太夫三味線 鶴澤津賀寿

企画制作:メメントC

批評(藤木直実)

Japanese Review By Naomi Fujiki

「女人往生環−女性を廻る救済と芸能の曼荼羅」に寄せて 藤木直実

プロジェクト「女人往生環」とは何か。それは、女性にとっての「往生」すなわち「救済」をテーマに掲げ、女性劇作家による女性登場人物に焦点化した脚本、すべて女性の邦楽家による伴奏、フェミニズム・ジェンダー批評など、多方面からその大きなテーマに迫り構成する、「曼荼羅」的演劇表現の試みの謂いである。第二回目となるこのたびは、造形美術家・井桁裕子の参加も得て、仏教説話に取材した「パターチャーラー」「韋提希」の二作品を上演する。いまから約二千五百年前、ブッダと同時代を生きた彼女たちのライフストーリーはどのようなものであったのだろうか。

時代はやや下るが、紀元前二世紀から紀元後二世紀ごろに成立したとされる『マヌ法典』は、ヒンドゥー社会の世界観と、ふたりのヒロインに課せられた規範を知る手がかりとなる。人類の始祖を意味する「マヌ」を冠し、宗教・道徳・習慣を包摂する細かな生活規定を説いた本書は、女性の生き方について次のように述べる。

「子供のときは父の、若いときは夫の、夫が死んだときは息子の支配下に入るべし。女は独立を享受してはならない」。

「夫は、性悪で、勝手気ままに振る舞い、良い資質に欠けていても、貞節な妻によって常に神のように仕えられるべし」。

すなわち法典の説く道徳や倫理は、そのまま社会における男性優位のジェンダー配置を固定化する論理として機能している。他の文化圏においても事態は大きくは変わらず、それぞれの宗教の聖典にはジェンダーの掟を内包する物語が随所に配備されて、人々のライフスタイルやアイデンティティをかたり、かたどり、かたちづくってきた。嶽本あゆ美の脚本は、仏教説話によってあまねく知られた女性たちの物語=表象をジェンダーの視点から読み解き、語り直し、現代社会に架橋する。

パターチャーラー尼は、ブッダの最初の女弟子として著名である。若き日、美貌と情熱を備えた彼女はカースト制度の戒律を破って、下賤の男と恋をする。その結婚は無残な結末を迎えるが、それでもなお損なわれぬ彼女の美貌は男たちを惹きつけてやまない。女性の「美」、言い換えれば男性の欲望を喚起する性的魅力は、諸宗教においてはしばしば悟達や救済すなわち「(男性の)往生」の妨げとして意味づけられる。とりわけ仏教では、性と生殖にかかわる女性の身体機能は「汚れ」とされ、「女人往生成り難し」のイデオロギーは女性の本質として人々に内面化された。

パターチャーラーの説話は、奔放で過剰な女のセクシュアリティを抑圧する挿話群に満ちている。彼女の被った苦難は支配文化が彼女に与えた懲罰であると見なされよう。欲望の主体(すなわち男性)を免責し、その欲望の対象(すなわち女性)に内省を強いる言説。事態は転倒にほかならないが、しかしこうした言説の機構は、装いを変えながら古代ヒンドゥー社会から現代日本社会にまで連綿と存在している。物語の末尾で、ひとりの女=母が、いまは高名な比丘尼となったパターチャーラーにその数奇な人生の因果を問いかける。再演にともなう改稿によってこの母は韋提希夫人に重ね合わされ、「パターチャーラー」を底流する「子殺し」のモチーフは「韋提希」に引き継がれることになる。

「韋提希」は仏説「王舎城の悲劇」を典拠とするが、これには史実の裏付けがあるとされている。インドのマガダ国の首都王舎城で、王子阿闍世がその父である頻婆娑羅王を殺害し、王位につく。新王はやがてブッダに帰依しその庇護者となったという。事件は「涅槃教」「観無量寿経」ほか複数の仏典に記載され、それらの注釈書や、親鸞の「教行信証」、また「今昔物語」によって、あるいは古澤平作と弟子の小此木啓吾が提唱した「阿闍世コンプレックス」の出典として、日本においても広く知られている。韋提希夫人はその阿闍世を産んだ母である。

阿闍世事件自体はきわめてエディプス的な性質を帯びていると言えるが、嶽本の脚本は父子の対立よりも母の葛藤に焦点を当て、家父長制が女性に強いる「産むこと」への重圧と「若さ」を喪うことへの恐怖、女性同士の競争反目関係、あるいは母親のみに課せられた重い養育負担を浮き彫りにする。ところで、仏教が女性救済のために発明したロジックとして知られる「変成男子」説は、女人成仏の条件としての男子への変身と、それを可能にする仏の功徳を説くものである。つまり、女性自身にその身体への嫌悪感を内面化させる一方で、仏教への帰依、言い換えればそのホモソーシャルな価値観やシステムの維持にすすんで貢献することを求めている。

社会にとって都合の良い様態への変成を強いられるのは女性ばかりではない。阿闍世のスティグマ、すなわちその「曲がった小指」は、男性の生に降りかかる構造的圧力の徴候と見なされよう。なぜ生まれ、いかに生き、どこに向かうか。阿闍世の問いはわたくしたちすべてに突きつけられた問いでもある。 (2019年公演パンフレットより)

批評(藤木直実)英語訳

Review (translated to English) By Naomi Fujiki

"The Cycle of Women's Rebirth in the Pure Land - Mandala of Salvation and Performing Arts that circles around Women"

Naomi Fujiki

What is the project of "The Cycle of Women’s Rebirth in a Pure Land" It is an attempt at a "mandala" style of theatrical expression that approaches the major theme from many angles, with a script by a female playwright focusing on female characters, accompaniment by an all-female Japanese musician, and feminist/gender critique. For the second edition of the festival, two works, "Patacara" and "Vaidehi", based on Buddhist tales, will be performed with the participation of artist Hiroko Igeta. What was the life story of these women who lived at the same time as the Buddha some 2,500 years ago?

The Code of Manu, which dates from somewhat later in time, around the second century B.C. to the second century A.D., provides clues to the worldview of Hindu society and the norms imposed on the two heroines.Bearing the name "Manu," meaning the founder of mankind, this book, which explains a detailed code of life that encompasses religion, morality, and customs, describes the way of life of women as follows.

"When you are a child you should be under your father's control, when you are young you should be under your husband's control, and when your husband dies you should be under your son's control. Women should not enjoy independence." "A husband should always be served like a god by his chaste wife, even though he is vicious, acts selfishly, and lacks good qualities."

In other words, the morality and ethics preached by the Code function directly as a logic that fixes the male-dominated gender arrangement in society. The situation is much the same in other cultures, where the scriptures of various religions contain stories that incorporate gender codes and have been used to describe, shape, and mold people's lifestyles and identities. Ayumi Dakemoto's script reads and retells from a gender perspective the stories of women who have been widely known through Buddhist discourses, and bridges the gap to contemporary society.

Patacara Nun is famous as Buddha's first female disciple. As a young woman, with beauty and passion, she breaks the precepts of the caste system and falls in love with a man of lowly birth. The marriage ends badly, but her unspoiled beauty still attracts men. Female "beauty," or in other words, sexual attractiveness that arouses male desire, is often seen in religions as an obstacle to enlightenment or salvation, or male attainment of Buddhahood.In Buddhism, in particular, women's bodily functions related to sex and reproduction were considered "unclean," and the ideology of "women cannot attain Buddhahood" was internalized by the people as the essence of women.

Patacara's sermons are filled with a group of eposodes that repress unbridled and excessive female sexuality. The hardship she suffered could be seen as a punishment inflicted on her by the dominant culture.A discourse that exonerates the subject of desire (i.e., men) and forces the object of desire (i.e., women) to introspect. The situation is nothing short of a reversal, yet these discursive mechanisms have existed in a continuum, in different guises, from ancient Hindu society to contemporary Japanese society. At the end of the story, a woman, the mother, asks Patacara, now a renowned bhikkhuni, about the cause and effect of her strange life. In the revised version, the mother is superimposed on Mrs. Vaidehi, and the motif of "child murder" that underlies "Patacara" is carried over to "Vaidehi".

"Vaidehi" is based on the Buddhist theory "The Tragedy of Rajagaha" which is said to be supported by historical facts. In Rajarha Castle, the capital of Magadha, India, Prince Ajase kills his father, King Bimbisāra, and ascends to the throne. The new king eventually took refuge in Buddha and became his protector. The incident is mentioned in "Nirvana Sutra" "Amitabha Sutra" and several other Buddhist scriptures, and is described in their commentaries, in Shinran's "Kyogyoshinsho" and "Konjaku Monogatari," and is widely known in Japan as the source of the "Ajase Complex" proposed by Furusawa Heisaku and his disciple, Okonogi Keigo. Mrs.Vaidehi is the mother who gave birth to Ajase.

Although the Ajase case itself is extremely Oedipal in nature, Dakemoto's script focuses on the mother's conflict rather than the conflict between father and son, highlighting the pressure on women to give birth and the fear of losing their youth, the competitive rivalry between women, and the heavy burden of childcare placed solely on the mother. By the way, the theory of "transformation into men," known as the logic invented by Buddhism for the salvation of women, explains the transformation into men as a condition for women to become Buddhas, and the Buddha's merit that makes this possible. In other words, it requires women themselves to internalize their aversion to their bodies while at the same time seeking refuge in Buddhism, or in other words, willingly contributing to the maintenance of its homosocial values and system.

It is not only women who are forced to metamorphose into a form more convenient to society. The Ajase's stigma, or the "crooked little finger," can be seen as a symptom of the structural pressures on men's lives. Why are we born, how do we live, and where do we go? Ajase's question is a question that confronts us all. From the 2019 performance brochure

批評(アリス・ワンダラー)英文

English Review By Alice Wanderer

A review of The Cycle of Women's Rebirth in the Pure Land Project

Alice Wanderer

Drawing on ancient texts, The Cycle of Women’s Rebirth in a Pure Land by Ayumi Dakemoto is a challenging, constantly surprising piece of theatre captured on film. It combines modern Noh drama techniques, touches of butoh and even borrowings from Indian dance with contemporary family drama to suggest the traumatic cycles of rebirth and the escape from these. The script uses a range of registers including piercing lines of poetry.

The first scene opens on a dimly lit rectangle on a theatrical stage. Four female musicians sit on a dais along the back. Behind them is a folding screen and behind that the deepest possible black shadow. Two male narrators also sit in front of low lecterns on stage right in profile to the audience. Accompanied by sparce drumbeats and exclamatory cries from deep in the body, a female dancer, Emi Nakae, head bowed, enters. She is dressed in a gauzy black, hooded cape and very slowly walks into the middle of the stage, faces the narrators, raises her head and then with such small steps that it is as though she is turned on a carousel, faces the audience and steps forward. The narration, a creation story, begins. The dancer, accompanied by a wailing flute, begins with strongly restrained slow movements punctuated by explosive jumps to enact the story with the black cape representing the darkness from which the universe emerges.

Once the gods, stars, seas, mountains, words and passions had been created, Brahma, “grandfather of the universe” divided “making one half a man and the other a woman.” The first child, Manu, a boy, is “the first human being” is also a creator who gives rise to all living creatures “constantly dancing in pleasure and pain”. Manu is also a lawmaker, and the “good” are instructed to follow his laws.This is a paradoxical prologue for a story of women’s rebirth in the Pure Land. The Laws of Manu are Hindu, not Buddhist, in origin and they authorize harsh caste distinctions as well as extremely contemptuous attitudes towards women. On the other hand, both Jōdu shū founded in the late 12th century by Hōnen in and Jōdo Shinshū founded by Hōnen’s disciple Shinran, the two Japanese Buddhist sects that centred exclusively on hope for rebirth in Amida Buddha’s Pure Land, welcomed women and people from every rank and class as equals.

Perhaps one connection can be seen in the black cape that plays such an important part in the first dance. As well as primordial darkness it could also represent Mappō. This is a Buddhist term for a time of degeneration and decay during which no one can reach enlightenment. The conviction that they were living in Mappō – characterised by famine, civil war and a conspicuous absence of enlightened people - inspired Hōnen’s and Shinran’s reforms. Instead of meditation, scholarship and monastic life only possible for a few, it was enough to whole-heartedly recite the Nenbutsu: Namu Amida Butsu.

The second part of Dakemoto’s cycle, also draws on an Indian story, is also danced and acted by Emi Nakae. Patacara, the ravishingly beautiful daughter of a wealthy man elopes with a servant and has two sons by him. The compelling nature of this attraction across caste boundaries is illustrated by her description of her body as “gold” and he as having skin “shining like a blue-black horse”. Patacara is the one who takes the initiative, rejecting the “lies of Manu”.

But she has also internalized these lies. So, despite her happy marriage she rebels at the idea of her children being “slaves” and heads back towards her parents’ home. The attempt to regain her privilege leads her to losses of Job-like proportions.Abused and shunned she traverses many kinds of hell until arriving at Jetavana Monastery she calls on Amida and welcomed, renounces the burning world. Remembering her former lives, she becomes aware of a terrible crime she once committed which accounts for all her subsequent suffering. The ending is unsettling to the degree that her appalling suffering is presented as inevitable and deserved.

Nevertheless, the play does bring attention to the story of woman who was a contemporary of the historical Buddha who – and this is only hinted at by Dakemoto – became an arhat (a person enlightened in this life), like many of Buddha’s male disciples. What are we to make of the fact that arhats, are Theravadins, a tradition that long precedes and rejects the doctrine of the Pure Land? The historical Patacara certainly did not recite the Nenbutsu. More importantly, and again this is not referred to in the play, but as Dakemoto may expect her audience to know, Patacara is regarded as the foremost female expert in the rules and procedures that govern monastic life. Perhaps this achievement can be interpreted as a subversion of the Law of Manu.

Patacara’s story is particularly important in the context of the thirty-year plus history of the struggle of Theravadin and Tibetan Buddhist nuns to get ordination, and it has been the subject of a 2010 novel and two more recent films from Sri Lanka and Nepal. Here though it is presented to a Japanese audience, which may account for the ahistorical Mahayana flavour.

Patacara’s reference to the burning world is a conventional Buddhist trope. Nevertheless, I was vividly reminded of Greta Thunberg’s 2019 speech to the World Economic Forum. We do not understand our times as Mappō, but we are aware of mass extinction and that unprecedented suffering is in the offing. As Hōnen and Shinran offered to their times, we too are in urgent need of radically new responses.

The story of Queen Vaidehi, the second one in the cycle is also based on an Indian story set in the time of the historical Buddha. In the first scene Vaidehi, powerfully played by Yōko Kanze, appeals rather aggressively to Buddha, demanding to know what sin she must have committed in a former life to give birth to her son, the usurper and parricide, Ajase. It becomes clear that she is confined, imprisoned by Ajase for trying to save his father who he had shut away to starve to death. A woman both courageous and ruthless, what Vaidehi has done is something she very well knows that she has done. And gradually is it revealed to the audience.

Much of the action is, however, taken up by a contemporary version of Vaidehi, also played by Yōko Kanze, who has been confined by her son in an old people’s home. The action begins when the father, against whom the son admits holding a grudge, is dying in hospital. It quickly becomes apparent that this old woman has not only psychologically vitiated this, her surviving son, but that she is frozen in time by pathological grief. The trauma is intergenerational, extending to her grandson and ending her family line.

Again, in extremis, both versions of Vaidehi reach a deeper understanding of life and death. If the queen, like Patacara, lives in a world of extremes, what Melanie Klein would have called the paranoid schizoid position, the contemporary Vaidehi and her daughter-in-law manage, eventually, to hold the contraries in creative tension.

Every woman sits on a large scale that is made by another…sometimes she falls into a situation where she must be seated with evil

Given its unresolvable griefs, dilemmas and impurities

Preaching love for the world is the most difficult thing to do

In the early days of the foundation of Jōdo shū, Hōnen, preached to and gained inspiration from the outsiders, artists, actors and artisans in Kyoto. Zeami, the inventor of Noh drama, was one such. The Nenbutsu could be a kind of theatre and Hōnen stressed the sacred nature of the human voice. Dakemoto’s inspiration and the synthesis of her achievement are both solidly rooted and widely ranging.

Alice Wanderer

Lives and works in Melbourne. She is a haiku poet and translator/researcher of Hisao Sugita.

Winner of Touchstone Distinguished Books Awards for 2021 by The Haiku Foundation.

“Lips Licked Clean: Selected Haiku of Sugita Hisajo”

(Translated by Alice Wanderer. Winchester, VA: Red Moon Press, 2021).

批評(アリス・ワンダラー)日本語訳

Review (translated to Japanese) By Alice Wanderer

「女人往生環プロジェクト」レビュー

アリス・ワンダラー

古代のテキストに基にした嶽本あゆ美による「女人往生環」は、挑戦的で驚嘆の演劇作品を映像に収めたものである。この作品は、現代の家族ドラマに、能の手法、舞踏のタッチ、さらにはインド舞踊からの引用を組み合わせ、トラウマ的な「輪廻」と、そこからの脱出を示唆している。脚本は鋭い詩句を含む幅広い領域にわたるものである。

最初のシーンは、薄暗い長方形のステージで始まる。四人の女性邦楽奏者が壁に沿ったひな壇に座っている。背後に屏風があり、そこには限りなく深い漆黒の影が映る。二人の男性の語り手(地謡)も、観客に横顔を見せ舞台右側に座している。鋭い大鼓の音と、身体の奥から発される掛け声を伴われ、女性ダンサー・なかええみ、がうつむいたまま入場してくる。彼女は、ゴージャスな黒いフードのマントを纏い、非常にゆっくりと舞台中央に辿り着く。そして語り手である地謡と向き合い、頭を上げるとまるで回転木馬のように旋回し細かなステップで、観客に向き合うと舞台前へと進む。天地創造のナレーションが始まる。ダンサーは啜り泣く能管を伴奏に、強く抑制されたゆっくりとした動きで始まり、爆発的なジャンプを挟みながら、黒いマントで宇宙が生まれ出る闇黒を表現し物語を演じる。

神々、星、海、山、言葉、愛欲が創られると、「宇宙の祖父」であるブラフマーは自ら「半身を男に、もう片方を女に」分割する。そして生まれた最初の子供であるマヌは、「最初の人間」であると同時に、「絶えず喜びと苦しみに踊る」すべての生き物を生み出す創造主でもある。そしてマヌは法律を司り、「善人」は彼の法律に従うように指示される。

これは、女性の極楽往生の物語としては、逆説的なプロローグである。マヌの法は仏教ではなくヒンドゥー教に由来し、厳しいカースト差別や女性蔑視の姿勢が公然のものである。一方、阿弥陀仏の浄土への往生のみを願う、十二世紀末に法然が開いた浄土宗と、法然の弟子である親鸞が開いた浄土真宗は、女性もあらゆる身分の人も平等に迎えていたのである。

最初のダンスで重要な役割を果たす黒いマントにも、一つの関係性が見られるかもしれない。原初の闇であると同時に、「末法」を表しているのかもしれない。これは仏教用語で、誰も悟りに達することができない退化と衰退の時を意味する。飢饉や内乱、悟りを開いた人々の不在が目立つ「餓鬼道」に生きているという確信が、法然や親鸞の仏教改革を促したのである。瞑想、学問、出家生活といった一部の人にしかできないことではなく、ただ心から念仏を称えればよいのである。「南無阿弥陀仏」

第二場面も、同じくインドの物語を題材に、なかええみが踊り演じている。大富豪の娘パターチャーラーは、使用人と駆け落ちし、二人の息子をもうける。カーストの垣根を越えるこの魅力の説得力は、彼女が自分の体を「黄金」と表現し、彼の肌を「青黒い馬のように輝いている」と表現することからもわかる。パターチャーラーは率先して「マヌの嘘」を否定している。しかし、彼女もまた、その嘘を内面化している。そのため、幸せな結婚生活にもかかわらず、自分の子供が「奴隷」になることに反発し、両親のいる実家へ戻る。自分の特権を取り戻そうとするあまり、彼女はヨブ記のような喪失を被ることになる。

(夫から)虐待され、疎まれた彼女は様々な地獄を経巡り、ジェタヴァナ僧院にたどり着き、阿弥陀仏を称えて迎えられ、灼熱の世界を放棄する。彼女は自分の前世を思い出しながら、かつて犯した恐ろしい罪の重さに気づき、それが後世の苦しみの因果となっていることを知る。この結末は、彼女の苦しみが必然であり、当然であるかのような印象すらも受けるものであり、不安にさせられる。とはいえ、この劇は、歴史上の釈迦と同時代の女性が、釈迦の多くの男性の弟子たちと同じように阿羅漢・仏弟子(現世で悟りを開いた者)になったという物語に注目している。阿羅漢がテーラワーディン(上座部仏教)であるという事実をどう考えればよいのだろうか。テーラワーディンは浄土教よりも長く先行する仏教で、浄土教を否定してきた伝統をもつ。歴史上のパターチャーラーは、確かに念仏を唱えてはいなかった。もっと重要なことは、これも劇中では言及されていないが、嶽本は観客が知っていることを期待しているのだろう---パターチャーラーは僧侶の修道院生活を支配する戒律や手続きに精通した第一人者の「女性」と見なされていることである。おそらくこの功績は「マヌの法」の破壊と解釈できるだろう。

パターチャーラーの物語は、テーラワーディンとチベット仏教の尼僧が(再び)受戒できるようになるまでの30年以上の格闘の歴史の中では、特に重要なコンテクストであり(注1)、2010年の小説やスリランカとネパールの最近の2本の映画の題材にもなっている。しかし、本作は日本人の観客を対象としているため、歴史的な大乗仏教の香りがしないのはそのためかもしれない。

注1(比丘尼回復運動・10世紀までで途絶えた上座部仏教での比丘尼の受戒やサンガの復活を願う活動。女性の尼僧としての得度の権利が上座部仏教において解決されていない。)

パターチャーラーが言及する「灼熱の世界」は、仏教の常套句である。それにしても、グレタ・トゥンベリの2019年の世界経済フォーラムでのスピーチを鮮明に思い出した。私たちは末法として、我々の時代を理解しているわけではないが、大量絶滅を意識し、未曾有の苦しみが迫って来ていることには気づいている。法然や親鸞がその時代に捧げたように、私たちも根本的で新しい対応を急務としている。

二作目の韋提希(ヴァイデヒ)王妃の物語も、釈迦の時代を舞台にしたインドの物語がベースになっている。最初の場面で観世葉子が力強く演じるヴァイデヒは、簒奪者であり謀反人でもある息子・アジャセを産んだのは、前世に自分がどの様な罪を犯したからなのかと問い、強い調子で仏陀に訴えかける。彼女は監禁されていて、阿闍世により、餓死させるために閉じ込めていた父王を救おうとした結果だということが明らかになる。

「勇気と冷酷さ」を併せ持つ女性であるヴァイデヒは、自分の行為について、自分自身でよく理解している。やがてそれは徐々に観客に明らかにされていく。しかしそのアクションの多くは、同じく観世葉子演じる現代版のヴァイデヒ(息子によって老人ホームに閉じ込められた母)が担っている。息子に恨まれている父親が病院で死のうとしているところから物語は始まる。この老母は、残された息子である彼を精神的に蝕んだだけでなく、悲嘆にくれたまま時間を凍結させていることがすぐに明らかにされる。トラウマは世代を超えて、孫にまで及び、家系が途絶えてしまう。

ここでもまた極限状態において、双方のヴァイデヒが共に、生と死についてより深い理解に到達するのである。女王がパターチャーラーのように両極端の世界、メラニー・クラインが偏執的分裂病的立場と呼んだであろうものに生きているとすれば、現代のヴァイデヒとその嫁は、最終的には、相反するものを創造的緊張の中に保持することに成功するのである。

「すべての女性は、他の人が作った大きなスケールの上に座っている...時には、悪と一緒に座らなければならないのです」

解決できない悲しみ、ジレンマ、濁りを考えると

「世界に対する愛を説くことは、最も難しいことである」

浄土宗の開祖・法然は、創建当初、京都の非人、芸術家、役者、職人たちに説教し、インスピレーションを得た。能楽の発明者である世阿弥もその一人である。念仏は一種の演劇であり、法然は人間の声の神聖さを強調した。嶽本のインスピレーションとその成果の総合は、しっかりとした根を持ちながら、幅広いものである。

Alice Wanderer(アリス ワンダラー)

メルボルン在住。俳人であり杉田久女の翻訳者・研究者でもある。

著作

“Lips Licked Clean: Selected Haiku of Sugita Hisajo” Translated by Alice Wanderer

批評(佐藤壮広)

Review By Takehiro Sato

©2022 MEMENTO C